Introduction

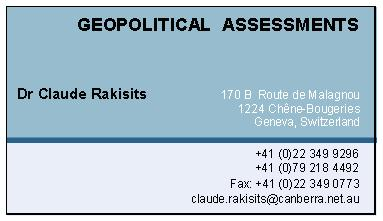

Dr Claude Rakisits (1956) was born in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo and holds the Australian and Swiss nationality. He holds a PhD in Political Science and a B.A (Hons) in International Relations.Dr. Rakisits is specialized in Pakistan and Africa and currently works as Adjunct Professor in International Relations at Webster University (Geneva). He is also head of “Geopolitical Assessments”, an independent consultancy whose core business is to provide analysis and advice on international issues: Geopolitical Assessments

Dr Claude Rakisits (1956) was born in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo and holds the Australian and Swiss nationality. He holds a PhD in Political Science and a B.A (Hons) in International Relations.Dr. Rakisits is specialized in Pakistan and Africa and currently works as Adjunct Professor in International Relations at Webster University (Geneva). He is also head of “Geopolitical Assessments”, an independent consultancy whose core business is to provide analysis and advice on international issues: Geopolitical Assessments

Article

Afghanistan and Pakistan: among the ‘hottest’ geo-political spots

The combined countries of Afghanistan and Pakistan, and in particular, their common border area, must be one of the ‘hottest’ geo-political spots in the world today. And this should come as no surprise, as it is in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of western Pakistan that the leaders of al-Qaida and the Afghan Taliban fled to following their ouster from Afghanistan in 2001 and continue to threaten the Coalition forces (International Security Assistance Force – ISAF) in Afghanistan and prepare attacks against Western interests in other parts of the world. It is also the home of the Pakistani Taliban who have caused much trouble in FATA and the bordering areas of Pakistan for the inhabitants and the government. It is precisely because this tribal area has become such a volatile region that the US administration and other Western countries have begun to refer to this area as “AfPak” and have appointed ambassadors to focus specifically on developments in that region.

The emergence of the Pakistani Taliban

What was already a difficult situation in “AfPak” has now become critical as a result of the recent and very worrying developments in the western part of Pakistan. In brief, what has happened is that the Afghan Taliban militants have ‘contaminated’ the local population with their jihadist extremism and this has in turn spawned an indigenous Taliban movement in Pakistan. Being of the same ethnic group – Pushtun – as the Pakistanis, it was not difficult for the Afghan Taliban to indoctrinate the locals. Moreover, many of these locals had themselves been involved in fighting the Soviets in the 1980s as Western-backed ‘Mujahideen’. These Pakistani Taliban – a mixed bag of religious extremists, thugs, petty criminals and fellow travellers – have not only effectively taken over control of the whole tribal areas (about the size of Switzerland), but they have now spilled into the ‘settled’ (non-tribal) areas of western Pakistan. And until recently, when they spilled into the beautiful Swat Valley and surrounding districts, these Taliban fighters were only about 100 kilometres from Islamabad, the nation’s capital.

The rising power of the Pakistani Taliban

The Pakistani Taliban’s fast expanding area of control has been facilitated by a number of factors.

First, the previous government under General Musharraf cut several deals with them hoping to stop their advance. But instead of disarming and expelling their allies, the foreign militants which include al-Qaida, as they were meant to, they consolidated their positions and evicted the army from the tribal areas.

Second, the army did not have the will or the counter-insurgency skills or materiel to fight back. Instead, the poorly-trained army lost over 1500 men, became very demoralised, and gave up.

Third, America’s use of drones to target high value Afghan Taliban militants and al-Qaida leaders hiding in Pakistan’s tribal areas has caused scores of civilian deaths among Pakistanis. This has reinforced already strong anti-American sentiments among Pakistanis, making it even easier for the Taliban to recruit among an already disaffected and economically deprived population. It is important to remember that in terms of socio-economic standards, FATA is not only by far the worst-off area of Pakistan but due to a number of historical reasons it is also not politically integrated with the rest of the country. Put differently, FATA has been for all intents and purpose forgotten by the central government in Islamabad since 1947.

Fourth, the Pakistan government’s February 2009 agreement – now dead – to allow the Pakistani Taliban to implement Sharia law in the Swat valley confirmed in the eyes of many that the political leaders in Islamabad only believed in appeasement and did not care about the well-being of the local inhabitants. For months already the Pakistani Taliban had been burning girls’ schools, forcing the closure of barber and video shops and hanging people by lamp posts if they disagreed with their version of Islam. Accordingly, as the people were given no protection from the authorities – the military not being anywhere to be seen and the police force resigning en masse out of fear – had no choice but to abide by the harsh rule of the Pakistani Taliban. Of course, it is important to remember that it was only after the army had failed to subdue the militants after one year of military operations and only cause civilian casualties and physical destruction that the government agreed to this February deal.

The limits of the Pakistani Taliban

However, the Pakistani Taliban’s fortunes have changed recently for a number of reasons.

First, the Pakistani Taliban broke their agreement with the government by not only failing to disarm as they were meant to do, but by continuing their advance eastward and spreading fear and destruction to neighbouring districts.

Second, this rapid and threatening advance eastward ever more closer to Islamabad caused all political parties and most importantly, the military, to realise that something had to be done to halt these militants whose objective was the overthrow of the government of Pakistan. However, even with this dire situation and notwithstanding a number of (unhelpful) alarmist assessments, the Pakistani state was not about to fall in the hands of the Taliban. The Pakistani Taliban, a disparate collection of jihadist groups without a unifying leader and little fire power, is no match for a 700,000 – strong Pakistani army.

Third, the US administration put enormous pressure on the Pakistani leaders, making clear that it expected the Pakistan army to roll these militants back and chase them all the way back into the tribal areas. Washington made clear that this would be a prerequisite for Pakistan to receive the economic and political aid it was seeking from the US.

The response of the Pakistani army

Accordingly, the Pakistani army decided in April to confront the Pakistani militants and to not only stop their advance eastward but to push them back into FATA. By mid-June it had secured the Swat Valley and the surrounding districts of Dire and Buner by ousting the 8,000 or so Pakistani Taliban fighters (which included hundreds of foreign and al-Qaida fighters), killing well over 1,000 of them and capturing the major city of Mingora. It took almost two months and some 40,000 troops to do the job, with well over 100 soldiers killed in the clashes. This was an important battle the Pakistani army had to win to demonstrate its resolve and capability.

But victory came at a very heavy cost to the civilian population. Because the army is primarily trained and equipped to conduct conventional warfare, it used a very heavy-handed and inappropriate approach to fighting the insurgents. By using heavy artillery, helicopter gunships and fighter bombers, it wrecked havoc on towns and villages, killing many civilians and destroying a lot of private property and the little infrastructure that existed.

The military operation in Swat caused some two and half million people to flee and seek refuge elsewhere. This massive and sudden movement of people was the biggest the world had witnessed since the 1994 Rwandan genocide. About 80 per cent of these internally displaced people (IDP) have been accommodated with friends, families and even total strangers because the government of Pakistan was unprepared for this humanitarian disaster. And while there has been a public mood change in support of the government’s military campaign, this could very quickly change if the government fails to help rebuild what it destroyed and resettle the millions of IDPs quickly. Analysts estimate that the reconstruction could cost up to US$3 billion.

Given that Pakistani President Zardari’s government is already inherently weak due a number of inter- and intra-party disputes, a failing economy and a lack of clear government direction or leadership on major policy issues, it cannot afford to fail in its military campaign against the Pakistani Taliban. The next step – the battle for Waziristan – will be crucial for Pakistan’s future and the direction of the war in Afghanistan.

South Waziristan

Even before ousting the Pakistani Taliban from Swat, the Pakistani army was under very heavy pressure from Washington to turn its attention to South Waziristan – the home base of the Pakistani Taliban as well as probably one of the most important safe havens for the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida. Accordingly, on 14 June 2009 the Pakistani government announced that a “comprehensive and decisive operation” would be launched to eliminate the Pakistani Taliban. But the forthcoming military clash in Waziristan will not be as easy as in Swat. As a matter of fact, it will be long, very difficult and nasty and costly in men and materiel. Already the Americans are ‘softening’ up the area with an increasing number of drone attacks against high value Taliban and al-Qaida commanders.

South Waziristan is very mountainous and rugged, with deep gorges and steep slopes, making it ideal insurgency country. There are no big settlements and towns like in Swat. As this is the Pakistani Taliban’s heartland, its militants will fight hard, and they will be doing so on home ground as opposed to Swat, where they were outsiders. They can expect a certain degree of support from the local population which will not look kindly at the Punjabi-dominated Pakistani army – seen as foreigners – coming in uninvited and inevitably bombing innocent civilians. And, as in Swat, the military operation will inevitably cause hundreds of thousands to flee the war zone to seek refuge elsewhere in Pakistan. This will further complicate the already grave humanitarian situation in western Pakistan where it is estimated there are some 3 million IDPs.

The role of the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida in Pakistan

Complicating the task of defeating the Pakistani Taliban is the presence of the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida which will no doubt give military support to their ideological brothers-in-arm. Moreover, having moved into the area some eight years ago after having been ousted from Afghanistan, the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida have had time to dig themselves in by building tunnels, hideouts and fortifications. They will be waiting for the Pakistani army.

They will all fight very hard: the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida to protect this very important launching area for attacks against Coalition forces across the border in Afghanistan and the Pakistani Taliban because losing Waziristan would be a fatal blow to their campaign to overthrow the Pakistani government. We can expect many more suicide bombings – now an almost daily occurrence – against state institutions (army bases, police stations, politicians) and innocent civilians across Pakistan in retaliation for the army’s military campaign.

Future prospects of the Pakistani Taliban

The good news for the Pakistan government is that the Pakistani Taliban is divided. There are a number of Pushtun leaders (some of them on the Pakistani government’s payroll) who want to eliminate or replace Baitullah Mehsud, the current leader of the Pakistani Taliban. One of these opponents, Qari Zainuddin, was assassinated on 23 June 2009. No one claimed responsibility. But, even if Baitullah Mehsud (suspected of having organised the assassination of Benazir Bhutto in December 2008) were eliminated or replaced as leader, it would not mean the end of the Pakistani Taliban threat. The government may try to exploit traditional tribal rivalry by giving military support to leaders of the Ahmedzai Wazir tribe. Such an approach could, in the long term, be dangerous and backfire, as tribal loyalties vis-à-vis the central government tend to be fluid.

But, even more important is the change of attitude of the Pakistani army. There is now a national consensus to oppose the Taliban (as opposed to under President Musharraf). Accordingly, the army is now determined to do the job that is required of them.

The outcome of the battle for Waziristan will have a critical impact on the current war in Afghanistan, and this is why the member countries of ISAF will be following very closely the course of the forthcoming battle in this tribal area.

Deteriorating conditions in Afghanistan

The situation in Afghanistan remains precarious at best.

On 12 June 2009 General David Pretaeus, head of the US central Command, admitted during an address he gave in Washington that conditions were deteriorating in Afghanistan and had been doing so for the last two years. As of 22 June 2009, Coalition forces had already lost 149 men this year, making it the worst first six months since military operations began in Afghanistan in late 2001. He stressed that the only solution to winning would be an integrated ‘whole of government’ approach which combined military operations with civilian needs. He also warned that there would be difficult times ahead. Most analysts tend to agree that the eight year-old war in Afghanistan is probably not even at the half-way mark. Almost 1200 Coalition defence forces have been killed since 2001.

Policy response of US president

In an attempt to make progress on the battlefield, President Obama agreed to send an additional 21,000 troops to Afghanistan. When this new ‘surge’ of defence personnel is in theatre, it will mean that the US will have some 68,000 troops in Afghanistan. Over 28,000 of these will be part of the ISAF forces (International Security Assistance Force) and the other 40,000 will be part of the separate US anti-terrorism operation, Enduring Freedom.

There is a worry, however, especially among Pakistani officials, that the surge could have a negative spill over effect, causing the Afghan Taliban fighters to flee across the border into FATA which in turn could create more Pakistani IDPs (internally displaced people).

The position of the Taliban

Unfortunately, as a result of the continuing poor security situation in Afghanistan, especially in the east and the south, the reconstruction process has not progressed as well as planned. Moreover, the very high level of corruption in the 82,000-strong police force and in the judiciary means that the people do not trust the government of President Karzai.

Accordingly, many people have, out of desperation, turned to the Taliban for assistance or support in the delivery of justice, social services and protection from the police and corrupt officials. Moreover, the high number of civilian casualties and substantial property damage as a result of Coalition military operations has facilitated the recruitment of new Taliban fighters among an ever growing pool of disaffected civilians. And while the Afghan government, with the help of the Coalition forces, is trying to build up a new Afghan army which would eventually number 134,000, up from the 90,000 today, Taliban fighters continue to be better paid than are Afghan soldiers. And while the Afghan army is relatively free of corruption, the quality of its officers and troops remains mixed.

Relations between Karzai administration and Coalition governments

The Afghan government’s high level of corruption and incompetence has greatly annoyed the Coalition governments, as it is becoming increasingly difficult for them to justify to their electorates the casualties and fatalities suffered by their troops in Afghanistan. The US, Canada and the UK have absorbed the highest number of dead.

It is important to remember that when NATO returned to Afghanistan in large numbers in 2003, the military involvement began as a peacekeeping operation but it quickly developed into a combat one. And while the ISAF-contributing countries generally hold President Karzai responsible for the Afghan government’s rampant corruption and incompetence, they have decided to continue to support his re-election bid simply because there is no one else that would be, on the whole, acceptable to the majority of Afghans.

Call for regional approach

If the international community, and in particular, the ISAF countries are to make substantial progress in restoring durable peace in Afghanistan and in large parts of western Pakistan, it will have to pursue a genuine regional approach to a war that now has ramifications far beyond the borders of Afghanistan and Pakistan. As President Asif Ali Zardari succinctly stated in an article in The Washington Post on 22 June 2009, “if the Taliban and al-Qaeda are allowed to triumph in our region, their destabilizing alliance will spread across the continents”. President Obama has also recognized the need for a regional approach and has made several statements along those lines.

However, this regional approach – which should include an international conference at which countries like India, Russia, China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, the Central Asian countries, the European Union and the US would be present – must be genuine if it is to succeed. It must be a process in which decisions that are taken and implemented have the support of Afghanistan and Pakistan and are backed up financially and militarily by the countries involved in the process. By having a stake in the outcome, regional countries will be more inclined to ensure the process works.

Financial support is vital

It cannot be sufficiently stressed how important the financial aspect of this approach would be to its success. Over many years Pakistan has paid a very dear price for playing a key role in the West’s involvement in Afghanistan. First, following the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, Pakistan hosted some four million refugees and was the training ground for many US and Saudi-backed Mujahideen groups battling the Soviet troops. Many of these Mujahideen and their off springs eventually turned against the Pakistan state. And since 2001, when the Pakistan government agreed to join the “War on Terror”, the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida fighters, embedded in western Pakistan following their ouster from Afghanistan, have been fighting the Pakistani army – a military clash that has tied down over 100,000 troops and has caused the death of well over 1,500 Pakistani soldiers. This is more than all the Coalition fatalities in Afghanistan.

Also, the international community must not forget that Pakistan still hosts some three million Afghan refugees, some of which are the ones caused by the Soviet invasion in 1979. And the present Afghan conflict has cost Pakistan’s economy – directly and indirectly – more than $35 billion. These are financial resources which could have been directed more productively to the socio-economic development of Pakistan.

But more importantly, the presence today of the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida fighters and the earlier presence of the Mujahideen in the tribal areas have been critical factors in the growth of Pakistan’s own Taliban group in the last few years. And it is this group, which has thrived in the utterly economically neglected tribal area of Pakistan, which has caused such havoc lately in Pakistan, particularly in Swat.

The Pakistan army conducted the ruthless operation in Swat and neighbouring districts because it was under intense international community pressure, especially from Washington and London, to do so. And as we have seen, the operation against these extremist groups has caused some three million IDPs (internally displaced people). Unfortunately, already the world is forgetting about them and the financial burden they are on the Pakistani government.

Dire humanitarian conditions

This on-going humanitarian crisis – and the one that will inevitably follow once military operation in Waziristan get into full swing – is something Pakistan cannot and should not have to deal with on its own. Of course, the Pakistan government had no choice but to confront militarily the Pakistani Taliban and roll them back. However, this was also an operation which was in the vital interest of the international community. It is in no one’s interest to see the Pakistan state being progressively weakened by a cancerous Pakistani Taliban gnawing away at Pakistani society. Accordingly, the international community has a duty to share the financial burden of not only assisting with the immediate reconstruction of the Swat valley but also with the longer term development of FATA and other socio-economically deprived parts of Pakistan where extremism thrives.

Pledged international support so far

Even before this latest flow of IDPs, Ambassador Holbrooke estimated that Pakistan would need some $50 billion in assistance to be able to deal with its massive developmental needs in such areas as social services, education, hospitals and infrastructure. In the short term, Washington’s decision to give $7.5 billion over five years for schools, the judicial system, parliament and law enforcement agencies should certainly help. Pakistan will also be receiving $400 million in annual military aid for 2010-2013 from the US. At the recent inaugural summit meeting between Pakistan and the EU, the latter offered $100 million in humanitarian aid to try to ease the burden of the 3 million IDPs; Pakistan was seeking $2.5 billion. At an international donors’ meeting in Tokyo in April 2009 Western countries pledged $5 billion.

Although this international assistance will help Pakistan, much more, however, will be needed in the long term given Pakistan’s war on extremism, the need to take care of three million IDPs, its massive developmental needs and the poor state of its finances. According to the Junior Economics Minister, Pakistan’s budget deficit is estimated to widen to 4.9% of GDP in the year starting on 1 July 2009. That’s higher than last year’s 4.3% and more than the 4.6% target set by the IMF as part of the 7.6 billion bailout agreed in November 2008. But the fiscal shortfall could actually end up being as much as 6.4% of GDP unless the government makes deep cuts on development expenditures which are already significantly inadequate. The government has asked the IMF for a $4 billion stand-by loan as “insurance” in case the pledged assistance does not arrive. Meanwhile, it is expected that the economy will grow by 3.3% in the year starting on 1 July 2009, which is better than last year’s 2% growth but significantly lower than the annual 6.8% Pakistan had posted for the preceding five years.

Pakistan’s point of view

Seen from Islamabad’s perspective, Pakistanis feel that, while US assistance will help as will the other countries’ aid, they are not getting the financial assistance they believe they rightfully deserve. They will argue, correctly so, that if the war against al-Qaida is so important to the West, why not give Pakistan the very substantial funds and military materiel they need to fight al-Qaida. The international funds that are being earmarked for Pakistan are miserly small compared to what has been spent by the US alone in Iraq in the last 6 years: some $600 billion or about $8 billion per month.

Trade liberalisation also critical

However, more important than aid is trade. And it would appear that the US Congress may relatively soon pass a bill called the Reconstruction Opportunity Zones, which would remove trade barriers and provide economic incentives to build factories, start factories and employ workers in FATA and in the neighbouring border area of Afghanistan. Such a concrete economic step would be a very constructive and important counter-insurgency measure for both sides of the border; it would demonstrate Washington’s long-term commitment to the economic development of the region and not only to the pursuit of a military solution to the problem of Islamic extremism.

Contact details of Mr. Rakisits