Introducing Gertjan Dijkink

Until his retirement in early 2011, Dr Gertjan Dijkink worked as Associate professor of political and cultural geography at the University of Amsterdam. He is also author of the frequently quoted book “National Identity and Geopolitical Visions: Maps of Pride and Pain”. This is part 2 of “Are There National Differences In Geopolitical Knowledge?”, the farewell speech he gave at the University of Amsterdam on 26 January 2011. You can go to part 1 by clicking on this link.

Until his retirement in early 2011, Dr Gertjan Dijkink worked as Associate professor of political and cultural geography at the University of Amsterdam. He is also author of the frequently quoted book “National Identity and Geopolitical Visions: Maps of Pride and Pain”. This is part 2 of “Are There National Differences In Geopolitical Knowledge?”, the farewell speech he gave at the University of Amsterdam on 26 January 2011. You can go to part 1 by clicking on this link.

A pdf file of the complete speech is available on Dr Dijkink’s website: “Are There National Differences In Geopolitical Knowledge?” (537 kB)

Article

Geopolitical traditions of The Netherlands, France and the United States

Geopolitical traditions of The Netherlands, France and the United States

The interesting question behind the observations in the first part of this article is to what extent a certain geopolitical myopia has settled in the Dutch genes or in those of whatever nation. There are nations or countries like France where geopolitics can traditionally account on some reverence.

My own experience in a French village of 200 souls is that you can actually stumble upon someone who is engaged in writing a geopolitical thesis, even the lady next door. The presence of geopolitical journals (Hérodote, Le Monde diplomatique) and the emphatic self-presentation of experts as geopoliticians is telling, certainly compared with the Netherlands.

Strangely enough the US also has been reproached of missing a geopolitical tradition: by none other than Henry Kissinger. The US would know a legalistic, pragmatic and idealistic but no geopolitical tradition. One may indeed say that the tenacious American tradition of dividing the world in good and evil is not the hallmark of sound geopolitical analysis.

Afghanistan, Pakistan and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA)

This discussion may easily fall back into small talk if we do not move over to empirical facts, in this case media research. For that purpose I want to take you to a battlefield that I have already mentioned briefly: Afghanistan. A true geopolitical analyst will never look at the struggle in Afghanistan as isolated, as something that is relevant within its border and for the rest perhaps only in terms of countries that may help or obstruct certain war aims.

From the early beginning the struggle with the Taliban could not be detached from the geopolitical nature of the region: Iran, Central-Asia, India and particularly Pakistan. These are not merely unitary players but states that have local groups of citizens with loyalties that overstep state boundaries and their international policies are multidimensional in such a degree that they easily appear paradoxical to the one that sees the struggle against the Taliban simply as a matter of liberating the Afghan people.

Pakistan was from the beginning (in 2001) on the screen because its support was essential in the logistics of war but when the Taliban was not defeated and Osama bin Laden not caught, attention automatically shifted to a new dimension: the wild frontier area between Pakistan and Afghanistan inhabited by equally wild tribes. These tribes would offer hospitality to the Taliban and Osama bin Laden because they have a tradition of autonomy and do not accept interference from outside, a situation even characterized as lawlessness.

At that time the word ‘tribal’ had acquired a special connotation in the Dutch public opinion because in domestic politics the ‘multicultural society’ was under attack evoking the specter of a society in which each group could make its own laws and rules. Here tribal clearly means dysfunctional.

The autonomy of the tribal regions, officially Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), was not that deeply desired by the local people. Federally Administered indicates that they are under direct supervision of the central government and do not have the right to choose their own (provincial) government which itself is represented in central government (this is the North-Western Frontier province or Khyber Pakhtunkwa as it is recently renamed). Authority in the FATA areas, that means administration of justice, is exercised by a political agent appointed by Islamabad who acts according to a colonial rule book, the Frontier Crimes Regulation.

In the FATA no elementary freedoms apply like freedom of speech and association, no laws to which one can appeal and consequently no access to justice and no protection of life and property. These are all results of a historic situation in which this region, and particularly Afghanistan, was a frontier, a buffer zone, between the British colonial empire and the Russian empire.

Pakistan’s frontiers, the Durand Line and the Inter-Services Intelligence agency (ISI)

The description of FATA is prototypical of imperial frontiers. It is an instable situation that characterized the historical frontiers of America (the Wild West), the region that separated the Austrian Empire and the Turks in the Balkans, and the back and forth between the Chinese Han dynasty and the Mongolian ‘barbarians’. After a period of British military pressure the then ruler of Afghanistan, Amir Yaqub Khan, concluded a treaty with the British (1879) in which important parts of Afghanistan like the FATA were ceded to British India.

The new borderline was officially demarcated in 1893 by the British-Indian Representative in Kabul, Sir Mortimer Durand. The treaty was concluded with British India and not with Pakistan that only burst on the scene in 1947. That is why Afghan governments have never recognized the ‘Durand-line’ after the secession of Pakistan. The use of the word Durand-line in our times indicates with a high degree of certainty that someone is referring to a contested border.

In view of the fact that Afghans claim Pakistan territory, one could imagine that it would be helpful to Pakistan if the border was endorsed in a multilateral agreement. Yet, and this the heart of the matter, Pakistan has never pressed toward such an agreement, not even at the time that such a thing would have been a logical extension of an international conference like the one held after the termination of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in 1988-’89. The deeper cause was that Pakistan, or in any case groupings around the power elite, deemed it useful to control an area to which international organizations or media did not have access. In this way they could exert influence across the border through the Pashtun ethnic group that lives in Afghanistan but also in large areas of Pakistan.

The organization that played a key role was the Pakistan intelligence agency ISI (Inter-Services Intelligence agency) that also had been an important tool in organizing terror against India in Kashmir. Some commentators have described these machinations as expressions of a country fighting to survive because Pakistan is threatened internally by a lack of national unity and externally on one side by arch-enemy India and on the other side by a very instable Central- and South-Asian region. Anyhow, Pakistan has always engaged in creating strategical depth in the direction of Afghanistan. You need to take account of these facts to understand why American attempts to put pressure on Pakistan – inciting them to take action in the FATA – were in vain.

Newspaper analysis: Dutch, French and US reporting on Afghanistan-Pakistan

Let us now consider these facts as frame of a geopolitical outlook and see what we can recognize of it in the newspapers of three countries: Netherlands, France and the US. The content analysis was based on four (quality) dailies in each country over the years 2002-2010.

Four quality dailies

- The Netherlands: Nederlands Dagblad, NRC-Handelsblad, Trouw, de Volkskrant

- France: Figaro, La Croix, Le Monde, Liberation

- US: Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post

The four Dutch newspapers published more than 1700 articles on the subject of Afghanistan (or the military operation in Uruzgan). These are all articles that mention the subject in their headlines. Many of these articles deal merely with political decision-making about participation in the war. Only less than 1000 articles pay attention to the terrain were the action is, that means experiences of the soldiers, the struggle against the Taliban and the attitude of the Afghan population. Among this category the number of articles that deal with the regional context, the role of Pakistan and the FATA is negligible, 43. The question is whether the other two countries show a keener geopolitical gaze in the news.

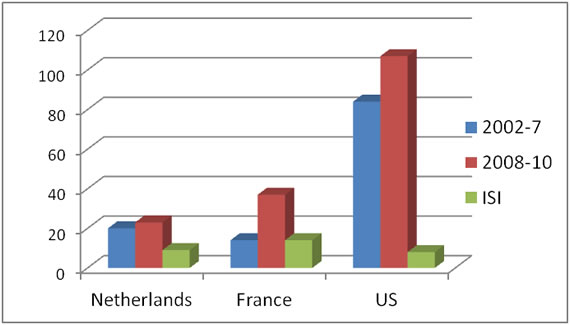

Looking at the entries for autonomous tribal areas (Figure 1), France does not cut a much better figure. In the first period (2002-7) French dailies even produced less news items than the Dutch newspapers. This may be caused by the fact that military operations on foreign soil are much more common in France. After 2007 French interest in the events in the border areas of Afghanistan and Pakistan surpasses the Dutch production of news.

However, the US media are by far the most productive on this theme. This is not surprising since the issue of the autonomous tribal areas is closely related with the hunt for Osama bin Laden. As remarked above, the existence of this frontier zone is only a part of the geopolitical story. The significance of the Afghan struggle for Pakistan is more clearly elaborated upon when the role of the Pakistan secret service (ISI) is included in the story. Here the US cuts a rather poor figure compared to the other countries (green column).

Figure 1 Number of articles that mention Pakistan, Afghanistan and autonomous tribal / federally (centrally) administered / FATA areas: Blue: 2002-7, Red: 2008-10, Green: number of this selection that also mention ISI.

France is superior, also when we look at attention for the historical dimension indicated by the number of references to the Durand line, the contested border (Figure 2). In the course of time the French media seem to focus more strongly on the geopolitical conditions of the war in Afghanistan whereas this theme gets less emphasized in the other two countries notwithstanding the penetrating analyses of the Pakistan journalist Ahmed Rashid whose book “Descent into Chaos” had just been published in 2008.

Figure 2 Number of articles that mention Pakistan, Afghanistan and Durand-line. Blue: 2002-7, Red: 2008-10

Conclusion: comparison of Dutch, French and American newspapers

The French emerge from this analysis as a nation with a geopolitical gaze while the Dutch gaze is perhaps not completely blind for geopolitical detail but somewhat myopic. However, a computer analysis based on key words may itself be myopic particularly when we are judging the ability to tell a coherent geopolitical story.

Such a thing can only be tested by a qualitative analysis: reading the entire article printed in a newspaper. This procedure yielded 5 articles in the Dutch press, 10 in the French press and 5 or 6 (depending on criteria) in the American press that could count as true geopolitical stories. This judgment is of course liable to criteria of this author but it is at least confirmed by the quantitative analysis.

It is further striking that the articles in the Dutch press that satisfied the criteria were not written by well-known prolific writers on international relations. They were from journalists in the field, a professor of South-Asian studies, and a former general-major teaching at an academy for International Relations studies. This shows how much a geopolitical perspective is promoted by (intimate) knowledge of the terrain rather than by a general knowledge of international relations and conflicts.