Introducing Gertjan Dijkink

Until his retirement in early 2011, Dr Gertjan Dijkink worked as Associate professor of political and cultural geography at the University of Amsterdam. He is also author of the frequently quoted book “National Identity and Geopolitical Visions: Maps of Pride and Pain”. This is part 1 of “Are There National Differences In Geopolitical Knowledge?”, the farewell speech he gave at the University of Amsterdam on 26 January 2011. You can go to part 2 by clicking on this link.

Until his retirement in early 2011, Dr Gertjan Dijkink worked as Associate professor of political and cultural geography at the University of Amsterdam. He is also author of the frequently quoted book “National Identity and Geopolitical Visions: Maps of Pride and Pain”. This is part 1 of “Are There National Differences In Geopolitical Knowledge?”, the farewell speech he gave at the University of Amsterdam on 26 January 2011. You can go to part 2 by clicking on this link.

A pdf file of the complete speech is available on Dr Dijkink’s website: “Are There National Differences In Geopolitical Knowledge?” (537 kB)

Article

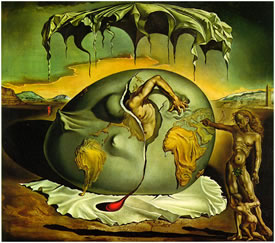

Salvador Dali’s ‘Geopoliticus Child Watching the Birth of the New Man’

In 1943 Salvador Dali painted the birth of ‘the new man’ (note: photo provided by author) as an event observed by ‘a new man’, the latter represented in the forefront and aptly named ‘Geopoliticus child’. Obviously I am not going to dwell on the esthetic qualities of paintings. Moreover Dali considered his own artistic capabilities mediocre: he attached more value to being recognized as a visionary genius!

In 1943 Salvador Dali painted the birth of ‘the new man’ (note: photo provided by author) as an event observed by ‘a new man’, the latter represented in the forefront and aptly named ‘Geopoliticus child’. Obviously I am not going to dwell on the esthetic qualities of paintings. Moreover Dali considered his own artistic capabilities mediocre: he attached more value to being recognized as a visionary genius!

My interest is of course in his vision, but let me nevertheless linger an instant over the esthetic aspects. Dali seems to revert to artistic conventions from the 18th century. According to these conventions the onlooker had to be guided into a painted landscape by something in the forefront: a human figure, a walker or a path. Here, in this painting, we see an adult person and a child in the forefront. Later on, artists like Caspar David Friedrich (see his Shipwreck from 1823) shocked the public by omitting such details, by slinging the onlooker smack down into the wilderness.

For them nature had to be experienced as an awe-inspiring reality, opposed to the human world. In Dali’s painting the shock is produced by something different: human nature, in this case the birth of a new geopolitical world order. It expresses the shift from European (mainly British) world power to American hegemony. We are faced here with relations between states but particularly with our misplaced idea that the world will always remain as it is now. Accordingly, it is not a bad idea to involve the onlooker by means of a human step as the old-fashioned pictorial rule recommended but now in the shape of (two) generations.

American world power and geopolitical knowledge

Today it is difficult to recognize the visionary quality of the 1943 claim that world power was disappearing from Europe because we tend to describe the advance of American hegemony as something that started even earlier. Nothing is easier than the wisdom of hindsight but I am rather thinking about geopolitical theories (or views) conceiving of world hegemony as a generational phenomenon that coincides with entire centuries.

Today it is difficult to recognize the visionary quality of the 1943 claim that world power was disappearing from Europe because we tend to describe the advance of American hegemony as something that started even earlier. Nothing is easier than the wisdom of hindsight but I am rather thinking about geopolitical theories (or views) conceiving of world hegemony as a generational phenomenon that coincides with entire centuries.

George Modelski and other writers described the sequence of world powers in history from Portugal in the 16th century, the Netherlands in the 17th century, Britain in the 18th and 19th centuries to the US in the 20th century. The idea of countries that leave their mark on a century became a hot topic of course at the close of the 20th century. Americans to whom the end of their hegemony was foretold, optimistically referred to the British who also could boast of two centuries.

Around the turn of the century many conferences raised the question of America’s hegemony in the near future. One of them, organized in Loughborough in 1999 by David Slater and Peter Taylor, was devoted to possible challenges to American world power. The conference didn’t particularly produce forecasts (although one speaker promised the US a Chinese-American 21st century at most) but rather attempts to identify the principles that had enabled the US to attain world power with the consequent question if such principles had become less powerful in the current global system.

Few participants in that conference were probably aware of the fact that neo-conservative intellectuals in the US already engaged in a Project for a New American Century aiming at realizing the second American century by means of a new worldwide military strategy. Their thoughts underlay the reckless American invasions after September 11 in Afghanistan and particularly in Iraq. Today’s evaluation is often that these strategies have helped to hasten the end of American hegemony rather than securing the start of a new American century.

What lessons can we learn about geopolitical knowledge? The important message is not that once in a century the world arrives at a turning point and that we cannot resist it. The message is rather that we should always start looking afresh at the way power is realized in a terrain. Being the biggest or military starkest does not mean much if you are blind to the terrain, the pattern of human and natural resources.

As the German father of political geography, Friedrich Ratzel, established in 1897: “one can only transcend the natural advantage of an adversary by entering his terrain with the tools with which he himself survives.” Applied to the rockets fired from drones at supposed Al Qaeda leaders at the frontier between Pakistan and Afghanistan this would imply a complete rejection of American (or NATO) military tactics.

The language of terrain, strategy and power, and the Dutch in Bosnia (UNPROFOR)

The language of terrain, strategy and power doesn’t come easily for the Dutch. That is not a very daring proposition. Dutch international politics has always stressed human rights, justice, development or ethic principles. I don’t have difficulties with that but rather with the fact that ethical ideals ultimately become frustrated when they are accompanied with poor geopolitical analysis. This may reduce such ethical principles to hypocrisy or, worse, produce the reverse of what has been aimed at.

Let me immediately give a dramatic example from the ethnic war in Bosnia where an explicit ethic principle (“chosing for life”) was pronounced in the context of the Dutch UN (UNPROFOR) operations. It is taken from an interview in the daily de Volkskrant from January 21, 1995:

[General] Couzy has returned [from Bosnia] extremely satisfied. “The men are still motivated and professionally engaged. This is the new Royal Army as I have in view. Over there we belong to the top of the premier league. UNPROFOR commander Rose has confirmed that it consists of the UK, France and the Netherlands.” […]

Up to now three soldiers have been killed on the Dutch side. Two soldiers have been seriously injured. Those are strikingly low numbers. According to Couzy, this is not merely a matter of good luck, training, equipment and discipline of Dutchbat have certainly contributed. […]

Dutchbat has a hard time in Srebrenica. The enclave, closed off from the outside world by Bosnian Serbs, is encircled by Serbian artillery and mortars. “They are trapped like rats. Therefore it makes no sense, to shoot firmly back during incidents like the freely moving British do. We have to do that well-balanced and deliberate” […]

The commander of the Bosnian Serbs, general Ratko Mladic, drives around in a Mercedes-jeep stolen from Dutchbat. Couzy:”That just sticks in your throat. Yet, it is one of the many harassments that one has to endure. Even if you were able to liquidate some robber captains then it would cost too many human lives. I choose for life.”

The sentence “I choose for life”, as ethically as it sounds in January 1995, would get a horrifying implication when these tactics permitted the murder on 8000 Bosniaks half a year later. In view of the genocidal impulses that already had manifested in the decomposing Yugoslavia, it was naïve to think that the symbolic presence of the much-harassed UNPROFOR troops would cast some weight in the balance with the ‘robber captains’.

Even if we establish that the Dutch (military commanders and policy makers) were not to blame (which is disputed) than the mere presence on the spot casts a slur on anyone’s reputation. Could it have ended otherwise?

A sharper awareness of the realities in the terrain might have induced the Dutch government to negotiate more heavy military guarantees from other NATO members when considering UNPROFOR participation. If the result had been negative, the absence of the Dutch on the scene or a more traditional conception of UN peacekeeping might at least have prevented the false sense of security that safe havens now induced in the Bosnian refugees.

Wrapping up part 1: the Dutch police training mission in Kunduz

Such a way of thinking that weighs capabilities against chances of success in a ‘battlefield’ is not the international approach of Dutch politicians who will never reconcile themselves to lack of power. The Dutch have replaced geopolitical analysis of success and failure with the primary goal to act in such a way that other members of the international community take account of them.

Even the most senseless contribution to the Western engagement with Afghanistan (the training of police officers that according to the agreement with the Afghan authorities have to abstain from military action in their further career) is accepted if it just helps the Netherlands to be recognized as a player on the international scene.

To continue with part 2, please click on this link