Introducing Iver Neumann

Iver B. Neumann is Montague Burton Professor at London School of Economics and also does research at NUPI. He is also adjunct professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences and a visiting professor at Belgrade University. His current research projects include cooperation with Serbian colleagues and a joint book project on the historical sociology of the Eurasian steppe with Einar Wigen.

Iver B. Neumann is Montague Burton Professor at London School of Economics and also does research at NUPI. He is also adjunct professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences and a visiting professor at Belgrade University. His current research projects include cooperation with Serbian colleagues and a joint book project on the historical sociology of the Eurasian steppe with Einar Wigen.

My New Book In 750 Words

1. What are the main themes of the book?

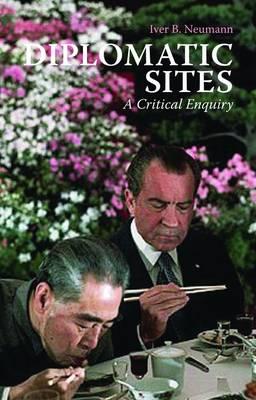

There are libraries full of literature on war, but only an uncrowded shelf with books on diplomacy. We know a lot about how polities fight one another, but not so much about how the communicate in other ways. The literature is dominated by diplomatic history, which focusses on the content of what is being communicated, and by autobiographies by diplomats, which tend to be self/aggrandising narratives about, well, very little. I try to contribute to a professionalization of this literature by looking at some typical kinds of encounter.

2. What are the central questions of the book?

That would be how these encounters are quotidian, embodied and sited, in the sense that they involve a lot of humdrum planning, meetings in the flesh and laying out of physical or virtual venues or sites.

3. How have you sought to answer these questions?

My major discipline is International Relations, but I also have a doctorate in social anthropology. I drew on ethnographic field work within the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and amongst the Corps Diplomatique of Oslo for periods that added up to three and a half years. I also drew on archival work and in-depth interviews.

4. What are the main findings of your book?

That would be how diplomatic sites like the dinner table or the media each have their understudied genealogies which involve general social practices – say, how Neolithic feasts transmute into ancient world feasts which then re-emerge as European banquets and then become the elaborate and highly stylised diplomatic dinner party. The general point here is that diplomacy is not, as common wisdom would have it, a self-contained system of communication, but that it is imbricated in general social practices. It is everyday social practices, and particularly the social practices of the dominant polities of the system, that give rise to diplomatic practices, and not the other way around.

5. What does the book contribute to existing literature in the field?

5. What does the book contribute to existing literature in the field?

Exactly that – that diplomacy is simply intensified, ritualised and exalted social work. The power differential is important for understanding ongoing changes, because it means that the rise of polities such as China, India and Brazil are bound to bring changes in specific diplomatic practices. On the other hand, the site genealogies demonstrate that diplomatic changes are indeed glacial, so there is little point in waiting for revolutions in diplomatic practices, as some of the scholars in the field who are always going on about how globalisation will remake everything often do. Globalisation is a very important change maker, but the changes it wreaks in the area of diplomacy are revisionist, not revolutionary.

6. How does the book relate to your own (personal/professional) background?

In International relations, so much scholarship is deductive; we often start with materialist models of the states system and/or the economic system, and assume this and expect that. As a reaction to that, the last two decades were dominated by hermeneutic and poststructural attempts at understanding actual preconditions for action. There was a textual turn, and I was part of it. Now that the textual turn has transformed the landscape, it is time to go back and re-examine materiality, and one way of doing this is in terms of practice analysis of the kind I try to execute here.

7. What further research into the book’s themes would you suggest?

7. What further research into the book’s themes would you suggest?

One key problem with studying diplomacy, and particularly what diplomats do when they are posted to their home Ministries, is field access. It is next to impossible to get access to the foreign ministries if you are not a national of that state. Therefore, we need research like this from more than one state in order to be able to generalise more about the changes in the diplomatic relations involved.