Introducing Alex Chitty

Alex Chitty holds a BA in Geography from the University of Brighton and is a master’s Student of Geopolitics, Territory and Security at King’s College London.

Alex Chitty holds a BA in Geography from the University of Brighton and is a master’s Student of Geopolitics, Territory and Security at King’s College London.

In this essay, he outlines the origins of the dispute in Western Sahara, and discusses the role of UN peacekeepers in the region.

The problems facing the longstanding ceasefire and seemingly distant plebiscite are explained, and conclusions drawn.

The problems facing the longstanding ceasefire and seemingly distant plebiscite are explained, and conclusions drawn.

The article

The Territorial Dispute in Western Sahara

Western Sahara is a territory in North Africa bordered by Algeria, Mauritania and Morocco, inhabited by Moroccan and minority indigenous Sahrawi populations. Formerly a Spanish colony known as Spanish Sahara, it is the site of an historical and ongoing territorial conflict between the Kingdom of Morocco and the Sahrawi rebel movement POLISARIO (the Frente Popular de Liberación de Saguía el Hamra y Río de Oro), supported by the government of neighbouring Algeria. A dispute characterised by colonisation, decolonisation, invasion and subsequent political deadlock has resulted in a situation which has in recent months been called “one of the longest, most intractable conflicts in Africa” (Mundy, 2009: 116).

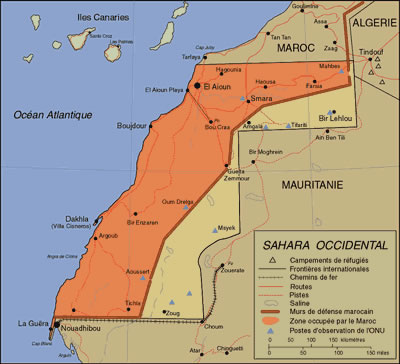

Currently de facto control of Western Sahara is divided into two areas; the larger western region (called ‘the Southern Provinces’ by Morocco, and the smaller eastern region known as the ‘Free Zone’ by the Polisario and Algeria (fig. 1). Despite extensive negotiations, a lengthy ceasefire and several attempts at UN mandated referendums on independence, as well as significant economic and political costs to the actors involved, (Northolt, 2008) the conflict has not yet been resolved.

Figure 1: A map of contemporary Western Sahara showing the two administrative areas held by Morocco and the Polisario (Public Domain image from wikimedia.org)

Origins

The origins of the Western Sahara conflict can be said to originate with the designation of the territory as a Spanish colony at the Berlin Conference of 1884 (Saxena, 1995). During Europe’s ‘Scramble for Africa’, Spain asserted its control of the coastal and inland regions of the Western Sahara as an area of strategic and military support for the Canary Islands and the lucrative fishing industry there. Spanish rule continued without significant international opposition through the first half of the twentieth century (Saxena, 1995), until the publication of United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1514 (the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples) which stated “the necessity of bringing to a speedy and unconditional end colonialism” and that “all peoples have the right to self-determination; by virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development” (United Nations, 1960).

Following this declaration, the Moroccan and Mauritanian governments took the opportunity to begin historically based claims to the region (Solà-Martín, 2006), and a period of ‘Transitional Administration’ began.

The Polisario

In reaction to Morocco and Mauritania’s historic claims, 1973 saw the formation of Polisario, the Algerian-backed Sahrawi rebel movement with the stated aim of establishing a sovereign state in Western Sahara (Pazzanita, 2006). In order to settle the dispute, the Spanish Government announced a referendum on independence, while the Moroccan government applied to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) requesting that it provide an Advisory Opinion (ICJ, 1995). The Spanish Referendum was postponed pending the results of the report.

After deliberation, the ICJ found significant Moroccan and Mauritanian historical ties to the region (Saxena, 1995) but noted that to divide the territory along these lines would not be in the interests of “self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory”, (ICJ, 1975: 1), and that historic claims were ‘irrelevant’ in the cause of self determination (Durch, 1993).

The ICJ report coincided with a UN Visiting Mission (UNVM), charged with investigating the political consensus in the region, and establishing the validity of the conflicting claims. The UNVM found ‘overwhelming’ support among the people of Western Sahara for independence, and in concurrence with the ICJ supported the establishment of a sovereign state in Western Sahara. While the Mauritanian government accepted the findings and withdrew all claims to the region (Durch, 1993), the Moroccan reaction and subsequent unarmed ‘invasion’ (Mundy, 2009) (known as the Green March) in 1975 formed the basis for the modern dispute.

In the years following the Green March, the Moroccan military established a network of high sand berms, initially demarcating a strategically important area in the north-west of the country (containing a number of phosphate mines), but gradually expanding forcibly to include around 85% of the territory, (Northolt, 2008), currently know as the Southern Provinces (fig. 1). This expansion was violently opposed by Polisario, equipped with modern assault rifles and vehicles by the Algerian government, who used guerrilla tactics to disrupt mining operations within the Southern Provinces.

Ceasefire

Since 1991, the Polisario and Morocco have agreed to a ceasefire under the auspices of a UN peacekeeping mission, known as MINURSO (the Mission des Nations unies pour l’Organisation d’un Référendum au Sahara Occidental). At the time this was considered to be “one of the most ambitious UN peacekeeping operations ever attempted” (Durch, 1993: 151) but has since become the focus for protracted disagreements over the electoral composition of the population.

The aim of MINURSO is to organise and conduct a referendum of the Sahrawi population, designed to offer a choice between sovereign independence and integration with the Kingdom of Morocco (United Nations, 1991). In addition to facilitating a plebiscite, MINURSO is charged with (source: minurso.unlb.org):

- Monitoring the ceasefire

- Verifying the reduction of Moroccan troops in the Territory

- Monitoring the confinement of Moroccan and Frente POLISARIO troops to designated locations

- Overseeing the exchange of prisoners of war (International Committee of the Red Cross)

- Implementing a repatriation programme (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees)

- Identifying and registering qualified voters

- Proclaiming the results of an election

- Taking steps with the parties to ensure the release of all Western Saharan political prisoners or detainees

Originally scheduled for 1992, the MINURSO referendum has not yet occurred because of an inability of the two sides to agree on the definition of the electoral roll. The Polisario suggestion of the 1974 census conducted by the Spanish government was blocked by Morocco, which had moved as many as 170,000 settlers into the Southern Provinces since that census took place. Morocco also attempted to add up to 250,000 Moroccan citizens to the list, with claims of other ties to the region (Northolt, 2008). One commentator in 1993 called the stalled process a “case study in the limitations of peacekeeping in the face of unalloyed nationalism and international indifference” (Durch, 1993: 168).

Sarahawi Autonomy

In an attempt to break the deadlock, in 1997 the United Nations appointed a UN Special Envoy and lead negotiator to Western Sahara named James Baker. Baker suggested a five-year period of Sahrawi Autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty followed by a referendum of all inhabitants who had resided in Western Sahara for at least a year, (called the Baker Plan, officially the Peace Plan for Self-Determination of the People of Western Sahara) but this was not accepted by the Polisario (Mundy, 2009). Baker then modified the plan in 2000 to allow only pre-1975 inhabitants to vote on local matters during the five-year autonomous period, but this was blocked by Morocco which formally proclaimed that Rabat would not accept any agreement which could lead to Saharan Independence rather than autonomy (Mundy, 2009).

Baker then resigned in protest to Morocco’s contradictory stance (Northolt, 2008). An assumption that autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty would be the most likely source of lasting peace in Western Sahara was the view of commentators between 2003 and the start of 2009 (Mundy, 2009; Solà-Martín, 2006).

Stalemate

In 2007 Morocco submitted an autonomy proposal to the United Nations which outlined a plan for a ‘Saharan Autonomous Region’ which was criticised by members of the international community, but supported by France and the United States government under George W. Bush (Northolt, 2008), frustrating the Polisario’s ultimate goal of sovereignty and cementing the autonomy consensus.

As stated by Mundy in early 2009, “the ideal situation is obvious enough…the will to achieve it will probably never coalesce so long as Morocco remains a steadfast ally of the United States and France” (p. 22).

Yet the future of Western Sahara may not transpire as predicted in recent years. In June 2009, the newly elected president of the United States Barack Obama wrote to the present King of Morocco, Mohammed VI indicating support for ongoing talks, but not reiterating the Bush-era support for West Saharan autonomy (Herald Tribune, 2009).

The conflict over Western Sahara has not been resolved satisfactorily in international law in the eyes of the Polisario or the Kingdom of Morocco. The proposed West Saharan independent state of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) is recognised by only 45-50 nations. The Arab League support Morocco’s claim to the region, while the African Union recognises SADR independence (AU, 2009). No state currently recognises Morocco’s present sovereignty over the entire territory, and Spain is still the de jure administrative power, though Morocco is the only de facto power in approximately 80% of the region (Annan, 2007).

Currently the status of the region is under review in ongoing negotiations supervised by the UN, four of which have taken place in Manhasset, USA (suggested as part of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1754), though these talks have yet to achieve meaningful gains, and the former UN Envoy for Western Sahara has stated in a newspaper interview that independence is ‘unrealistic’ (El País, 08).

Commentators suggest that with relatively insignificant political, economic and strategic assets at stake, the ‘international community’ may treat Western Sahara as a low priority in years to come (Mundy, 2009; Northolt, 2008; Saxena, 1995).

References

- African Union, (2009) Map of Member States [Accessed 22 September 2009]

- Annan, K (2007) Report of the Secretary-General on the situation concerning Western Sahara S/2007/619, United Nations. Original: English

- Durch, J. (1993) Building on Sand: UN Peacekeeping in the Western Sahara. International Security, 17(4), 151-171

- International Court of Justice (1975) Advisory Opinion of 16 October 1975 paras. 84-161 of Advisory Opinion

- Mundy (2009) Out with the Old, in with the New: Western Sahara back to Square One? Mediterranean Politics, 14(1), 115-122

- Northolt N.A. (2008) Fields of Fire – An Atlas of Ethnic Conflict. London: Northolt Communications

- Pazzanita (1994) Morocco versus Polisario: A Political Interpretation. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 32(2), 265-275

- Saxena, S.C. (1995) Western Sahara: No Alternative to Armed Struggle. Delhi: Kalinga Publications

- Solà-Martín, A. (2006) United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara. London: Edwin Mellen

- United Nations (1960) United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1514. United Nations S/1960/947 14 December 1960. Original: English

- United Nations (2007) United Nations Security Council Resolution 1754. United Nations SC/9007 31 October 2007. Original: English

- World Tribune (2009) Obama reverses Bush-backed Morocco plan in favor of Polisario state [Accessed 22 September 2009]

Pingback:Unilateral Declaration by Polisario under API accepted by Swiss Federal Council | Armed Groups and International Law

Thanks for the link, Katherine and Rogier. Kind regards, Leonhardt

Unfortunately, there are a number of factual errors in this report. First, there was no “Transitional Administration” in Western Sahara after the publication of Resolution 1514. Spanish Sahara continued to be a colony of Spain. What DID happen is that in 1966 Spanish Sahara was placed on the UN’s list of non-self-governing territories entitled to self- determination and de-colonization. Second, the discussion of the ICJ Advisory Opinion on Western Sahara is incorrect. If you read the Opinion you will note that the Court did NOT find “significant Moroccan and Mauritanian ties to the territory.” Just the opposite. It found that neither state had established any tie of territorial sovereignty over the territory and at most had shown that there were ties of allegiance between them and some of the people in the territory (paras. 107, 129,150) during some period of time. The Court concluded by stating “Thus the Court has not found legal ties of such a nature as might affect . . . self determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory.” (para. 162). The Court did NOT say that historic claims were “irrelevant” but rather that the type of “historic ties” offered by the parties were insufficient to constitute proof of sovereignty over the land and its people. Next, the Mauritanian government did NOT withdraw its claim to the territory after the publication of the report of the UN Commission in 1975. Rather, it joined Morocco in invading the territory later that year and only withdrew its claims in 1979 after being defeated militarily by Polisario forces. The invasion by Morocco was not the “Green March.” Even before the Green March took place Morocco sent troops into the territory which battled the Polisario forces. These battles in the latter part of 1975 started what was to become a 16 year war that only ended in 1991 when the Polisario agreed to a ceasefire that would allow a UN sponsored referendum to take place. Finally, what has impeded the implementation of the referendum was NOT a dispute over the criteria for eligibility to vote. Both parties agreed to eligibility criteria in 1994, and it was according to those criteria that a voters’ list was published in 1999. The reason why the referendum has not taken place is that Morocco saw that the voters’ list was not in its favor and that if a referendum took place on the basis of that list, it would probably lose. There are a number of other inaccuracies in this report, but these are the most important. Please don’t assume that everything you read about this conflict is correct — there is a lot of misleading information floating around — as well as outright lies. Katlyn Thomas, former Director of Legal Affairs, UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO).